R. Nelson Parrish: 21 Flags

Every nation has its own mythology, a legendary history of its founders meant to unite and inspire those who follow. King Gilgamesh of Ancient Sumer, Romulus and Remus of Rome, and King Arthur’s defense of Britain with his mighty Excalibur are but a few of the numerous examples. Without a doubt, George Washington is the key figure in the lore of the United States, and among the most iconic images of the brave general is Emanuel Leutze’s George Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851), painted 75 years after the fateful event. While historians debate on the accuracy of the details—would the Old Fox really be standing?—there is one fact most agree upon: that particular flag would not have been there. It was the Great Union flag, and not the familiar Star-Spangled Banner that would have accompanied old George on that fateful night.

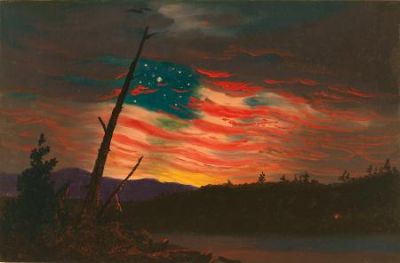

The United States flag has a mythology of its own, often celebrated in paintings that document turning points in the nation’s history. Leutze fully understood the patriotic appeal of the flag while toiling away on German soil to create his icon of Americana. This tradition continued in the able hands of Alfred Jacob Miller with his Bombardment of Fort McHenry (1828-30), a visual narrative to Francis Scott Key’s famous musical ode to The Star Spangled Banner, while Frederick Church later paid homage with his painting Our Banner in the Sky (1861), an allegoric sunset transformed into the famous tattered flag of Fort Sumter, where the Civil War ignited into full-scale war. More recently, the stars and stripes have become a means to critique and embody social and political unrest. In 1990, African-American artist David Hammons recast the familiar red, white and blue in the cloak of Marcus Garvey’s pan-African flag of red, black and green to highlight issues of identity and race in America with his African-American Flag. A few years later, Swiss-American Hans Burkhardt’s final painting, The Extra Stripe (1994), formed the flag from weathered burlap, replacing the field of stars with horizontal cruciforms, alluding to the casualties of war in protest of the U.S. involvement in the Middle East.

R. Nelson Parrish draws on this deep-rooted legacy in his exploration of the symbolism of the United States flag. His series of paintings, titled 21 Flags, is clearly based on the familiar pattern of stars and stripes, but abstracted nearly beyond recognition. By doing so, he compels the viewer to grapple with the scrapes, gaps and scratches while mentally reconstructing the familiar image hung vertically. The end result is neither a patriotic ode nor didactic lecture, but a process-driven technique that collectively speaks of the polysemic nature of the flag itself.

The series is a departure for the Alaskan-born artist, who is best known for his sculptural pieces, through which he deconstructs the opposition between man-made and the natural world. The works, which the artist terms “totems,” are fashioned from planed wooden planks wrapped in layers of transparent and color-infused bio-resin. The result is an upending of expectations: the natural objects become man-made geometric structures, while the languid flow of pigment is a result of natural forces. These works evoke the Finish/Fetish preoccupations of his West Coast forebears with a nod to Flow painting: John McCracken meets Peter Alexander meets Gerard Richter. The interaction of light with pigments suspended in the bio-resin slowly ebb and flow around the heart pillar of the individual works contrasted with hand-painted racing stripes, providing another layer of contrast to the mix.

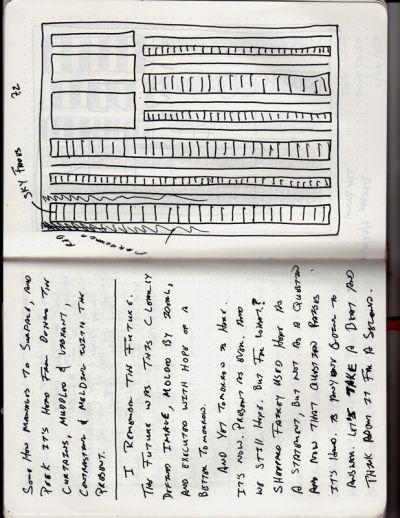

At the core of Parrish’s process is a love of experimentation. Never satisfied, the artist continually pushes his materials to the point of collapse, ironically creating his own set of problems to be solved. After breaking down the processes he had painstakingly developed over many years, Parrish began to experiment with the individual components of his work as isolated motifs. The stripes became a focal point. Removed from the luminosity of the transparent resin base, he explored color and technique, spraying thin layers of paint on paper before scoring a series of stripes across surface, revealing the triage of colors hidden beneath.

In strictly formal terms, Parrish’s 21 Flags are descendants of these painterly investigations. The artist recalls a moment of hesitation as he pushed the abstract patterns into a more familiar iconography. He challenged himself to the task, and sent an image of this abstracted national symbol to a trusted friend who advised: pursue this path only “if you’re making a statement.” After a sleepless night, he rose with a sense of renewed urgency: he needed to create more flags. Through this initial urge came a new motivation: to use the symbol of the flag as a vehicle to consider what exactly it means to “be American.”

From this initial moment of creation, Parrish began to question: what does the flag symbolize? For whom? He revisited his past, from his youth in the Alaskan Frontier—both part of America yet separate from the lower 48, to his life as a working artist in Southern California, his experiences as a husband and more recently, as a father. During this process, Parrish excavated old black-and-white photographs taken years earlier, inspired by the likes of Robert Frank and William Eggleston, as he journeyed across the American landscape. The photos are exploratory images, ranging from somber to mischievous to hauntingly nostalgic, documenting the diversity of American life and livelihood. Looking back, these photographs signify the starting point for the artist’s current body of work.

On the surface, it might seem appropriate to relate Parrish’s 21 Flags with the iconic images of the United States flags by Jasper Johns in the mid-20th century, paintings that have acquired a lore of their own. Johns, initially inspired by a dream, painted his first flag in 1955 and continued to explore the symbol as a subject for several decades. These works represent the artist’s rejection of the existential angst Abstract Expressionism, the first internationally recognized movement that put American painting on the world stage. Instead, in the early years of the Cold War, Johns employs an emotionally charged symbol to embark on a perceptual game: is it a flag or a painting? With a nod to this legacy—naming the second flag in the series Jasper—Parrish also flips the equation. Where Johns used the flag to talk about painting, Parrish uses painting to speak about America.

Although each of the 21 Flags are clearly identifiable as derived from the American standard, the intention of appropriation is left purposefully vague. The flags are not meant to conjure a specific event, but a broader view of the past and present. Once begun, the cumulative layers of spray paint have only minutes before the paint is set. Every mark made upon the surface leaves its own history. The scrapes and scars act not solely as interruptions of the national symbol; they are a source of aesthetic beauty. The jagged stripes and striations of color evoke the frequencies of radio waves, cell phone signals, and—by abstraction—the distortions of news and communication through social media. The hollows and gaps provide visual relief; yet speak to breaks in history, to moments of silence and censor. These variations will inherently provide room for differing interpretations, as Parrish pushes the familiar construction of the flag to the point of failure.

For Parrish, these works are at once communal and deeply personal. The images are probing, critical and yes, patriotic. Each of the 21 Flags is unique, ranging from tricolor pageantry to variegated exhilaration to monochromatic solemnity, but they are united as a whole. The flags present a dichotomy, the technique produces a rugged aesthetic, but as works on paper, they are delicate. This allusion to the complexity and fragility of democracy is both overt and unapologetic. For the viewer, the paintings provide a focal point to meditate upon the diversity of meanings embodied by this familiar symbol. As we are bombarded with news of riots, protests, natural disasters and divided partisanship, the flags provide a moment of solace to ponder this question of what it means, or what it can mean, to be American.

Essay by MOLLY ENHOLM. Enholm is an art historian, freelance writer and artist based in Los Angeles. She is the former managing/digital editor of art ltd. magazine and contributor to several online and print publications, including Art and Cake, ArtScene, Fabrik, Hi-Fructose and Visual Art Source. In addition to writing, Molly also teaches courses on Modern, Contemporary and Asian art history at California State University Northridge.

Image footnotes:

1: Washington Crossing the Delaware. Emaneul Leutze, 1851.

Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Muesum of Art.

2: Our Banner in the Sky. Frederic Edwin Church, 1861.

Image courtesy of Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

3: African-American Flag. David Hammons, 1990.

Image courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art.

4: Got to Go North. R. Nelson Parrish, 2017.

Image courtesy of Boat Yard Studios.

5: Scan from sketchbook.

Image courtesy of the artist.

6: Sly. R. Nelson Parrish, 2001.

Image courtesy of the artist.

7: Studio/process image. 2017.

Courtesy of the artist.